|

| The Independent Traveler's Newsletter PAGE THREE |

|

| The Independent Traveler's Newsletter PAGE THREE |

| FRANCO-AMERICAN

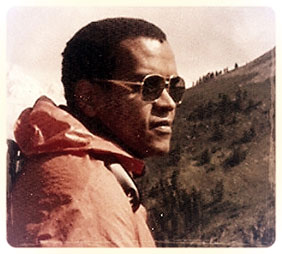

PORTRAIT - Kirby Williams, author of Rage in

Paris by Arthur Gillette Critically acclaimed, Rage in Paris is both an historical

and a crime novel, which has as its background the political,

anti-Semitic and racist turmoil in Paris early in February 1934, when extreme right-wing groups tried to seize the French National Assembly. Their aim was to install a government along the lines of Germany's, where Adolf Hitler and his Nazis had come to power a year earlier. Among the main characters are black and mixed-race American expatriates, including a number of veterans of America's segregated WWI army who have decided to settle in Paris instead of returning to the worsening racial climate in America. A number of these expatriates are the jazzmen who first brought the music to Europe while playing in all-black American Army jazz bands. Born in Oklahoma in 1940, the son of mixed-race Texans (black, white and native American) and after graduating from Hamilton College in upstate New York, its author, Kirby Williams, was drawn to Paris at the age of 22 and never lived again in the United States. Arthur Gillette recently interviewed him for this exclusive portrait for FRANCE On Your Own. A.G. Why did you leave the States quite young? And what so attracted you to Paris that you never moved back? K.W. After college I worked for the New York Department of Health early in 1962 and was sent with colleagues from all over the country to a training session at the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia. For my first lunch there, I, the lone black trainee, was sent away from my fellow students to eat in the cafeteria in the 'colored' wing of the publicly-financed Grady Hospital. Going into an upscale bar in the black part of Atlanta later that evening to drown my sorrows, I met a man who was leading the campaign to integrate Grady. I ended up telling him my story, we sent some press releases around and, the next day, the story of my treatment made the front pages of the national press. Senator Abraham Ribicoff of New York and my Harlem  congressman

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. were overseeing public health at the time and

threatened to cut off government funding for Grady and the Disease

Control Center unless the hospital was integrated forthwith . The

directors of my program in Atlanta arranged rapidly to have me made an

honorary white person for a day, which allowed the 'integration' of the

'white' cafeteria until Ribicoff and Powell ordered the New York

delegation to return to New York and suspended the operation until

Grady was fully integrated. The acrimonious struggle to desegregate

Grady Public Hospital continued until its integration was finally

achieved in the mid-1960s. congressman

Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. were overseeing public health at the time and

threatened to cut off government funding for Grady and the Disease

Control Center unless the hospital was integrated forthwith . The

directors of my program in Atlanta arranged rapidly to have me made an

honorary white person for a day, which allowed the 'integration' of the

'white' cafeteria until Ribicoff and Powell ordered the New York

delegation to return to New York and suspended the operation until

Grady was fully integrated. The acrimonious struggle to desegregate

Grady Public Hospital continued until its integration was finally

achieved in the mid-1960s. I never really settled back into New York and American life again after my 'escape' from Atlanta in mid-1962. In the ensuing months, I remembered the tales that my black Texan great uncle, who had served in France in WWI, told me when I was a child ~ about a place called France where he had been treated like a human being by the French. I always suspected that he regretted having returned to his dehumanizing life in post-WWI Texas instead of staying in France. I also remembered my readings of Ernest Hemingway, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and I set sail for Le Havre on October 5th, 1962, for what I expected to be a one-year stay in Paris. In fact, I never returned to America to live. Paris was not a color-blind Utopia and I arrived on the heels of the ending of the Algerian War when there was a pervasive climate of anti-Arab sentiment. Still, in the student milieu I moved in, contacts with French and international students were warm and intellectually stimulating, and I never felt the epidemic racism that was prevalent in America at the time in the North as well as in the South. A.G. What have you been doing in Paris for the last fifty-three years? And have you experienced racism here? K.W. When I arrived in Paris I was fluent in German having studied it since Junior High School, but my knowledge of French was limited to counting to ten. So, the first order of business was learning the rudiments of the language, which I managed to do in record time given the reluctance of the French to speak English at the time. I kept body and soul together by teaching English. Then I fell in love with a white student from England, was fortunate enough to land a job at UNESCO, got married to the love of my life, and raised a family. Both of our children are professionals living in the New York area. I retired from UNESCO in 2000 after 33 years of service, and my wife and I have spent the intervening years traveling, visiting our British and American families and generally enjoying life in France. France is inexhaustible ~ there's always a new city, village, monument or museum to visit. We also like talking to the French in the different nooks and crannies of the country that we discover. Contrary to popular belief, they are far from all being rude and grumpy! As for personally experiencing racism, when SHAPE was still headquartered in France and there were American GIs around, I heard about certain clubs and discotheques that were discriminatory. This was of a piece with what happened after the allied victories of WWI and WWII when American military as well as tourists flocked to Paris and France and did not feel comfortable in places with black patrons, thus 'forcing' the establishments to practice de facto discrimination. Later, there were reports of discrimination in Paris discotheques, but the French, to their great credit, have enacted stringent laws against discrimination in accommodations and against speech and expression that incite racial or religious hatred. I have never personally experienced discrimination in my 50 plus years in France, which is not to say that it doesn't exist. A.G. What do you like about Paris ~ best, moderately, not at all? K.W. My father, who was one of the first Americans to join the United Nations in 1946 and who traveled the world widely in its service, used to say to me: whatever you think about Paris (he was a committed Anglophile), it's impossible to be indifferent to her. I don't like Paris…I love Paris. I love its quarters, its street culture, its permanence and, at the same time, its modernity. Whenever I'm away from Paris for more than a few weeks, I get a hankering to return. As soon as I get back, I head out for an omelet, some cheese and some red wine! I really grew up here, and Paris enabled me to think of myself as someone who was not a 'hyphenated' American. Through living in Paris, I came to terms with what being an American means and it gave me the realization of how deeply my roots go into America, both into black America and white America. At the end of the day, I realized that Americans are, indeed, a people and a unique one. Of course, Alexis de Tocqueville had discovered American identity long before most Americans did! A.G. During your years here you've met such authors as James Jones, Langston Hughes and Gregory Corso, not to forget musicians like Bud Powell and Memphis Slim. In 1968 you also almost suffocated from tear gas during the police/student confrontations of 'The Events of May 1968'. How would you say your time in Paris has differed from the creatively roaring but also very troubled 1920s and 1930s of Hemingway’s Paris? K.W. Up to the end of the 'Events of May' in 1968, I don't think it differed enormously in its soul. The Latin Quarter and Montparnasse were filled with bookstores and student hotels and restaurants and cafés, and you used string bags to shop, and your vegetables and fruit would be wrapped up in old newspapers. You could buy a glass of wine and sit at your table in your café on Boulevard Saint Germain, Boul'Mich or Boulevard Montparnasse for hours and meet your friends, be introduced to writers, artists, students, eccentrics from all over the world. There were few of the comforts that we had in America even in the early 1950s, such as refrigerators, telephones, deodorants and even toilet paper. But there was something authentic about Paris and it was amazing how intellectual the young French university students and workers were. After May of 1968, France modernized and commercialized very rapidly. Like many people who knew the quarters I just mentioned up to the late 60s, I avoid them nowadays; they've become a vast shopping mall. I'm probably being a bit unfair. A.G. Finally, why did you pick the mid 1930s as your time focus for Rage In Paris? K.W. I have lived long enough and seen enough to recognize that there are many dark currents in the human psyche which persist in spite of the works of God and man. They can resurface at times of great social transition and upheaval. The mid 1930s were such a time, and we are living such times now. That's why I wanted Rage In Paris to be not only a crime and historical novel, but also a cautionary tale. I hope that we remember the lessons of the past; otherwise, as George Santayana said, we are condemned to repeat them. Published

by Pushcart Press/W.W. Norton in December 2014. Available in paperback.

ISBN-10 1888889764 & ISBN-13 978-1888889765 Amazon.com readers give it 4.5 stars and Publishers Weekly said, "A love of Paris and its people, including the poor and the crooked, comes through . . .as does a passion for jazz. A finely wrought story that depicts the violence of an era with a solid noir touch." SPONSORING THIS ISSUE This Normandy château is rented by the week, but there is much more! Themed weeks, escorted tours of Normandy or Champagne, and even transportation to the château from Paris airports can be part of your holiday. Enjoy nine elegant guest rooms, gourmet dinners - all at a very reasonable cost. Click on the photo to visit Château de Sommesnil to see all it has to offer. Contact us soon to make your reservation or for more information. |

|

LA GRANGE - an excerpt from Lafayette: His

Extraordinary Life and Legacy

by Donald Miller The following are

excerpts from our reader Donald Miller's 412-page biography,

Lafayette: His Extraordinary Life and Legacy, to be published this summer. Donald Miller, a journalist since 1956, has spent twelve years exploring Lafayette's role in three Revolutions - American, French and the July 1830 Revolution toppling Charles X of France.  ".

. .

Receiving

a passport through James Monroe and reaching Paris, Lafayette

immediately wrote Bonaparte and Sieyès that he had returned from

his post-prison retreat in the Netherlands. The first consul,

infuriated, saw Lafayette as a potential enemy leader or rallying point

of opposition. He had Lafayette watched and repeatedly tried to

win him over. Lafayette's wife, Adrienne, reclaimed her mother's Château de la Grange-Bléneau,

a turreted and moated thirteenth-century castle amid 800 acres about

forty miles southeast of Paris. After looking at nearby Château de Fontenay Trésigny,

also inherited from Adrienne's mother, the Lafayettes made La Grange

their refuge, turning Fontenay over the Adrienne's sister Pauline. ".

. .

Receiving

a passport through James Monroe and reaching Paris, Lafayette

immediately wrote Bonaparte and Sieyès that he had returned from

his post-prison retreat in the Netherlands. The first consul,

infuriated, saw Lafayette as a potential enemy leader or rallying point

of opposition. He had Lafayette watched and repeatedly tried to

win him over. Lafayette's wife, Adrienne, reclaimed her mother's Château de la Grange-Bléneau,

a turreted and moated thirteenth-century castle amid 800 acres about

forty miles southeast of Paris. After looking at nearby Château de Fontenay Trésigny,

also inherited from Adrienne's mother, the Lafayettes made La Grange

their refuge, turning Fontenay over the Adrienne's sister Pauline.". . . La Grange was close enough to Paris for occasional visits but far enough away to avoid confrontation with a government they came to despise. With little agricultural knowledge but admiring Washington and Jefferson's abilities, Lafayette slowly became a gentleman farmer in the Brie countryside with the help of an overseer and neighbors. He developed a large vegetable garden to feed his growing family, brought in fruit trees, chickens and livestock. He bred merino sheep, producing the region's finest wool. He also razed the château's west wing, opening it to a park he filled with important American trees and plants.

". . . At La Grange, Adrienne had a designer create for her husband a small Louis XVI-style library with a star-patterned parquet floor in a turret space next to his second-floor bedroom. Here he gathered his favorite books on curving shelves. Mementos included framed copies of the Declaration of Independence and Lafayette's Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. From his window Lafayette called daily instructions through a horn to his farm manager who was for many years his former army secretary and his servant at Olmütz Prison in Moravia, who later became tax collector of Fontenay.

Today,

a private French foundation oversees La Grange, only open to scholars

and writers.

FOOTNOTE TO OUR FRONT PAGE ARTICLE ABOUT L'HERMIONE: The French spent 17 years and $28

million, including the many donations, replicating L'Hermione down to

the last detail, from its gilded-lion figurehead to the fleur-de-lis

painted on the stern. The original Hermione was

built in 1779 and it, and its sister ship, Concorde, were the pride of the

rejuvenated French Navy. The Hermione,

that could outsail any ship at sea, was 216 feet long with a

copper-bottomed hull and 32 guns meant to take on the English.

They later captured the Concorde

and drew plans of the ship as they reverse-engineered it in order to

build something as grand for the English navy. These schematics

proved to be a Godsend to the French when, 200 years later, they

decided to build an authentic tall ship of their own since they were

the only seagoing nation without one! "In the

1980s, we restored the shipyards

at Rochefort, where l'Hermione was

built, and made them a cultural monument," says Benedict Donnelly, who

heads France’s Hermione project,

the Association Hermione-La Fayette, supported by public funds and

private donations. "But then in the '90s we said, we're missing

something. A recreated tall ship. France is really the poor relation

among nations in this department. The Hermione was

the jewel of the navy from a glorious moment in French maritime history

- which hasn't always been glorious, thanks to our friends the English.

Happily, our English friends had captured the Hermione’s

sister ship and left us the plans."

The Hermione under

construction in 2011 and the dry dock at Rochefort

We hope you will have the

opportunity to see this amazing vessel for yourself in the US or in

France and become a part of its incredible history.

|

previous

page

next page

previous

page

next page  |